Ashmolean Museum

Delftware plate of Queen Anne

(c) Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Date: c. 1702

Country of origin: Probably Bristol, England, UK

Accession number: WA1967.45.21

Location: Floor -1, Exploring the Past Orientation Gallery (1)

This typical commemorative plate depicts Queen Anne (1665-1714) as a stylised representation of womanly and royal virtues. Plates like this were an affordable way for people to display their loyalty to Queen Anne, who was a very popular monarch, celebrated as the ‘nursing mother’ of her people. However, she was also criticised by her political opponents for being influenced by her ‘favourites’ and she was sometimes accused of having lesbian relationships. Among the women in Anne’s life, the most significant was Sarah Churchill, Duchess of Marlborough. The relationship between them eventually broke down because of bitter quarrels over politics and Anne’s increasing closeness to her maid Abigail Masham. Enraged by Anne’s preference for Abigail, Sarah sponsored the anonymous publication of verses accusing the Queen of having a sexual relationship with Abigail. She then sent copies to the Queen, threatening Anne that she was risking her reputation over her passion for her maid.

Katie Hambrook

Images

$50 US banknote countermarked with the words ‘Lesbian Money’

(c) Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Date: Late 20th century

Country of origin: United States of America

Accession number: HCR6426

Location: Floor -1, Money Gallery (7)

The US gay and lesbian rights movements – which evolved throughout the 1970s towards the end of the 20th century – adopted many surprising and covert strategies of political protest and civil disobedience. One particular method of activism was to (illegally) stamp dollar bills with the slogans: ‘gay money’, ‘lesbian money’ and ‘queer $$$’. The circulation of the notes across the States draws on a long tradition of currency being defaced with political messages. As the notes are exchanged from hand to hand, they foster unexpected and intriguing encounters with the dissenting individual, who, in this case, stamped her money in purple – a colour broadly associated with 20th century women’s liberation movements – and the marginalised community of which she was a part. It is an understated, yet powerful, act of resistance, which makes it possible for lesbian voices, in particular, to be seen and heard.

Adrienne Mortimer

Read more about ‘Lesbian Money’ by Adrienne Mortimer

Money changes hands hundreds of millions of times in a single day. We usually know nothing about the former possessors of our banknotes. This $50 bill with the words ‘Lesbian Money’ stamped on it changes this. From the 1970s onwards, US-based LGBTQ+ activists began stamping words such as ‘QUEER $$$’, ‘Lesbian Money’ and ‘Gay Money’ on bills to bring attention to the presence and (economic) contributions of LGBTQ+ members of the community. A particularly notable campaign took place in the late 1980s when Chicago-based LGBTQ+ bar owners Marge Summit and Frank Kellas launched a campaign to stamp bills with ‘Gay Money’. It is estimated that more than $17 million were stamped as part of the campaign, which ended after the Secret Service sent a ‘cease and desist’ letter to them because defacing money in the US is a serious crime.

Michael Beauvais

Images

Seated figure of the bodhisattva Guanyin

(c) Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Date: 13th century

Culture: Buddhist

Country of origin: China

Accession number: EA1982.2

Location: Ground Floor, China to AD 800 Gallery (10)

This Chinese Buddhist figure is the Bodhisattva of ‘infinite compassion’ who remained in the world to ease suffering and help others to attain enlightenment. Loved by all Buddhist traditions, Guanyin can take many forms, appealing to a variety of people, to promote the understanding of the teachings of Buddhism. Bodhisattvas are generally presented as androgynous handsome males. However, this sculpture of Guanyin can be interpreted as either male or female, showing the figure’s transcendence beyond gender. In Mahayana Buddhism physicality of gender is considered a delusion of the unenlightened and in the 12th century Guanyin’s association with the tale of the ancient princess Miaoshan started the beginning of the gradual feminisation of this deity. This figure was constructed in 13 parts using furniture and building techniques, echoing Chinese architecture and would have occupied a dominant position in a temple hall, representing its universal and inclusive nature.

AKE

The image of the seated bodhisattva marks a transitional phase in the transformation of the male form of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara into the Chinese female deity Guanyin, the ‘Goddess of Mercy’. Avalokiteshvara was said to be the earthly manifestation of the Buddha Amitabha, whose figure can still be seen represented at the front of the headdress. Avalokiteshvara, often translated as "the lord who looks upon the world with compassion", was said to be able to appear in 33 different physical forms, seven of these as a woman or young girl. It is thought that Avalokiteshvara, with Buddhism, was introduced into China around the 3rd century BC. From his introduction until the Jin Dynasty (1115–1234) images of the bodhisattva were increasingly androgynous, incorporating both male and female characteristics. In China from the 12th century Avalokiteshvara is entirely represented as the female white robed Guanyin.

G R Mills

Read more about Guanyin by G R Mills

This wooden figure of the goddess of mercy Guanyin represents a bodhisattva who was represented as a male for several hundred years and then as a female. Guanyin began as Avalokiteśvara, an enlightened being who postponed his own transcendence to stay and help others on earth. Assuming over 30 different manifestations, both as a man and as a woman, Avalokiteśvara’s gender fluidity was a seen as a strength for it allowed the bodhisattva to better help both men and women. As Buddhism made its way over the Himalayas to China, Avalokiteśvara took on a more female form. The precise chronology of this transformation is unclear, however. Some scholars point to textual traditions showing female manifestations of this bodhisattva as early as the 7th century; others point to artistic representations showing Guanyin with characteristics which were not initially considered feminine, but which became so over time.

Michael Beauvais

Images

Athenian red-figure pottery cup

(c) Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Date: 500-401 BC

Culture: Ancient Greece

Country of origin: Found at Vulci, Italy

Accession number: AN1967.304

Location: Ground Floor, The Greek World Gallery (16)

This dish shows a homoerotic scene between two males of different ages. This behaviour was considered as "the principal cultural model for free relationships between citizens” [1], resulting in an expanded social network, beneficial for the boys and their families before marriage. Such relationships may have had their origins in an initiation ritual within military or religious life, encouraged by athletic and artistic nudity, or in the practice of delayed marriage between aristocrats, the social seclusion of women and even as a way of population control within a homosocial society. Athenian law recognised consent, but not age as a factor in regulating sexual behaviour. The age-range (15‐18) when the younger partner entered into such relationships was the same as for girls given in marriage. Boys, however, were usually free to choose their partner. ‘Red‐figure’ vase painting, like this, replaced the previous style of ‘black‐figure’, as red depictions were more realistic, although both were quite elaborate, using a three‐phase firing process.

Barbara Diaz-Navarro

Read more about this red-figure cup by Barbara Diaz-Navarro

[1] Dawson, D. 1992. Cities of the Gods: Communist Utopias in Greek Thought. Oxford University Press, New York, p. 193.

Images

White ground lekythos by the Achilles Painter

(c) Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Date: c. 475-425 BC

Culture: Ancient Greece

Country of origin: Athens, Greece

Accession number: AN1889.1016

Location: Ground Floor, The Greek World Gallery (16)

The domestic scene on this vessel shows two women, elegantly dressed and playing music together. They represent the female world of elite ancient Greek women in Athens, where this was made around the time the Parthenon was built, and in Lesbos, where the poet Sappho lived over 150 years earlier. Sappho's poems express her love for a series of women and celebrate the same-sex love affairs of her friends, giving rise to the modern use of the word ‘lesbian’. Her circle of friends played music and sang to each other; Sappho was really a singer-songwriter rather than a poet. Over time her music was lost and eventually even the lyrics were known only from quotations in the works of other writers. However, archaeologists discovered more of her poetry on scraps of papyrus excavated from an ancient rubbish dump at Oxyrhynchus in Egypt in the late 19th and early 20th century. These scraps of writing are kept here in Oxford and researchers have been painstakingly patching together more of Sappho’s lost lyrics ever since.

Katie Hambrook

Read about the Amazons by Victoria Sainsbury

[2] For example, Parkinson, R.B. 1991. Voices from Ancient Egypt: An Anthology of Middle Kingdom Writings. British Museum Press: London, p.120.

Images

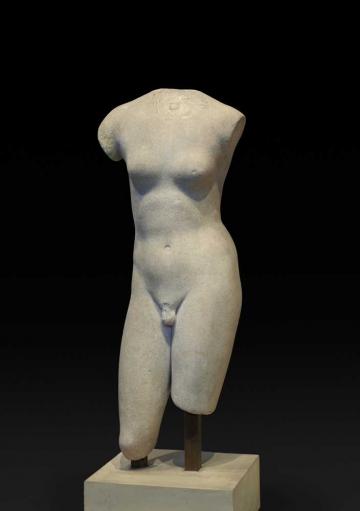

Marble statue of Hermaphroditus

(c) Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Date: AD 1-200

Culture: Ancient Rome

Accession number: ANMichaelis.34

Location: Ground Floor, Greek and Roman Sculpture Gallery (21)

In Greek mythology, Hermaphroditus was a deity of androgyny, sexuality and fertility. As the son of Hermes and Aphrodite, fused with Selmacis, a nymph, he became an androgynous figure - a combination of male and female characteristics. Importantly, Hermaphroditus was not portrayed as half woman, half man, but rather as a fusion of the beauty of both women and men. The sculpture is a demonstration of how the classical worlds of ancient Greece and Rome viewed sex and gender identity differently to the more common focus on gender binary often experienced in European society today. For example, the idea that you can only be a ‘man’ or a ‘woman’, and that these are opposing and separate, biological sex and gender identities. The idea of gender fluidity is now returning to the forefront of LGBTQ+ discourse, however.

The word ‘hermaphrodite’, meaning an organism that has fully formed sexual organs associated with both male and female anatomy, stems directly from this mythological character. However, the term is not used to describe humans as it is derogatory as well as clinically problematic.

Rebecca Wood

Read more about Hermaphroditus by Ela Xora (artist)

Images

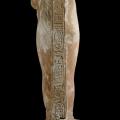

Model of a Seth animal

(c) Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Date: c. 3500-3400 BC

Culture: Naqada Period

Country of origin: Egypt

Accession number: AN1895.138

Location: Ground Floor, Egypt at its Origins Gallery (22)

No documents have survived that show that homosexuality was explicitly forbidden in ancient Egypt, but texts do show that it was still stigmatised. The penetrated partner was a Hmiw; ‘a back turner’ or ‘a coward’. To be penetrated was to become weak, as explored in the mythic tale The Contendings of Horus and Seth, the latter deity represented in this stone animal amulet. Using what has been claimed as the world’s first chat-up line, “what a lovely backside you have” [2], Seth attempts to penetrate Horus to assert dominance over his nephew. Wary of his plan, Horus fools Seth into thinking he has been successful. Eager to assert his own dominance, Horus coats Seth’s lettuce with his semen instead. Calling a tribunal of the gods to announce Horus’s defeat, Seth is then humiliated when it is revealed he has become the dominated one by unknowingly consuming Horus’s semen.

Ben Wilkinson-Turnbull

[3] Montserrat, D. 2000. Akhenaten: History, Fantasy and Ancient Egypt. Routledge: London.

Statue of Akhenaten

(c) Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Date: c. 1345-1335 BC

Culture: 18th Dynasty New Kingdom Amarna

Country of origin: Egypt

Accession number: AN1924.162

Location: Ground Floor, The Amarna ’Revolution’ Gallery (25)

For many, the ancient Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaten is the first gay icon. Amarna period art is famous for its intimate depictions of affection between Akhenaten and his wife Nefertiti. However, the discovery of a carved stela in the 1920s, showing Akhenaten affectionately touching the chin of another male figure, inspired generations of writers and painters to depict Akhenaten as homosexual. Other writers have interpreted the other male figure as Nefertiti, however. Akhenaten remains a queer icon though. His androgynous depiction in art, seen in the wide hips and prominent breasts in this limestone statue, has also led to suggestions that the pharaoh was intersex or had a genetic condition that affected his appearance. However, it is more likely that he cultivated an androgynous image of himself on purpose, in an imitation of the male and female attributes of his creator god, the Aten. Until his mummy is firmly identified, the debate is likely to continue.

Ben Wilkinson-Turnbull

This sandstone statue of the king Akhenaten contains many androgynous physical characteristics which have led to contemporary speculation on his gender and sexuality. Akhenaten was a progressive pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty, who introduced great changes to ancient Egyptian religion and art. Some scholars suggest that Akhenaten’s feminine physique may have been an attempt to portray himself as both the male and female divine, in imitation of the creator god he promoted, the Aten. By depicting himself as both and promoting the Aten almost monotheistically, he could replace the other gods, like Isis, Amun, Hathor and Tawaret, and become the all-seeing, all knowing, “mother and father of all human kind" [3]. On the other hand, some scholars have suggested that Akhenaten had a medical condition that changed his physique and contributed to his feminine appearance, but this also raises questions about how realistic ancient Egyptian art was. Recent studies of a mummy found in KV55, a tomb in the Valley of the Kings, believed to be Akhenaten by some Egyptologists, shows no signs of obvious physical deformity, however.

G R Mills

Read more about Akhenaten by G R Mills

[4] Ross, R. 1905. 'A Note on Simeon Solomon’, The Westminster Gazette, 24 August 1905, p.1-2.

Images

Manju netsuke showing the female warrior Tomoe Gozen and Wada Yoshimori

(c) Ashmolean Musuem, University of Oxford

Date: 19th century

Country of origin: Japan

Accession number: EA2001.67

Location: Floor 2, Japan 1600-1850 Gallery (37)

This netsuke (根付), a carved toggle used to attach purses to traditional Japanese dress, shows Tomoe Gozen (巴 御前) and her lover Wada Yoshimori (和田 義盛). While this beautiful example dates from the 19th century, Tomoe lived in the 12th century. Tomoe was known for extreme feminine beauty on the one hand, and unparalleled physical, masculine strength and courage on the other. She undertook the most male of professions by becoming a samurai (侍). In some tales, she is also a female entertainer, highlighting this contrast even more.

Semi-fictionalised accounts of Tomoe’s life became popular along with other stories that play with the notion of gender as performative – decided by actions and not biological sex – such as Torikaebaya Monogatari (とりかへばや物語, ‘The Changelings). Many females across history have assumed elements of masculine dress, nomenclature or gender, for a variety of reasons. They have acted in contrast to the behaviour their cultures have expected for their biological sex, against a corresponding binary gender, which can be viewed as surprisingly modern.

Victoria Sainsbury

Read more about Japanese netsuke and Noh masks by Victoria Sainsbury

Images

Bust of Prince Henry Lubomirski (1777-1850) by Anne Damer (1748-1828)

(c) Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Date: c. 1787

Country of origin: England, UK

Accession number: WA1908.208

Location: Floor 2, Arts of the 18th Century Gallery (52)

This bust is typical of Anne Damer’s neoclassical sculpture, praised by contemporaries for its simplicity and purity. By contrast, her wealthy and aristocratic circle gossiped about the impurity they saw in her relationships with other women. From 1776, when her unsuccessful marriage ended in her husband’s suicide, accusations about her lesbian relationships appeared in print. For the rest of her life, rumours about her kept re-surfacing. Her social position helped her endure these attacks, but they threatened her relationships with less aristocratic women, anxious about the impact on their reputations. Anne was deeply pained by the libels and gossip about her, but she never chose to live safely out of the limelight. She refused offers of marriage and she appeared on stage in private theatricals attended by the whole of London society. She took up sculpture, a masculine pursuit, and exhibited her work publicly, asserting her identity as an artist.

Katie Hambrook

Images

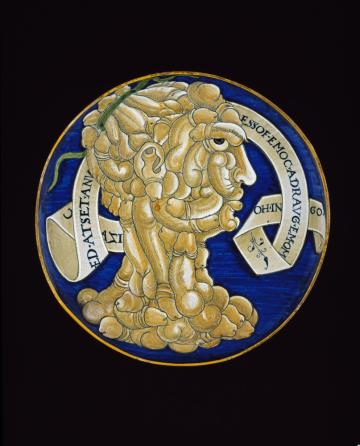

Dish with a composite head of penises

(c) Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Date: 1536

Artist: Probably Francesco Urbini (active 1530-1536)

Country of origin: Possibly Gubbio, Italy

Accession number: WA2003.136

Location: Floor 2, Arts of the Renaissance Gallery (56)

This unique ceramic dish, of the Bella Donna type, shows a human head composed of penises, with an earring and a hair band. Both features are traditionally feminine, but the earring also symbolises those groups of people considered as outsiders during the Renaissance, such as Jewish people and slaves. The inscription written on the scroll should be read right to left, like Hebrew, and translates as: “Every man looks at me as if I were a head of dicks”. The insult, ‘dickhead’, refers to a stupid or weak‐headed man who thinks with his penis rather than with his brain. The dish’s sexual ambiguity, social satire and, if the penises are interpreted as circumcised, anti‐Semitic overtones differ from other Bella Donna dishes, where graceful women are usually depicted. Painting on ceramics became highly valued as a fine art in renaissance Italy. Coloured oxides were skilfully painted on a white tin oxide background which was then fired in a kiln. The technique, known in Italy as maiolica, was first introduced into Spain by the Moors.

Barbara Diaz-Navarro

Read more about this maiolica dish by Barbara Diaz-Navarro

Images

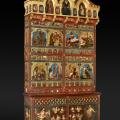

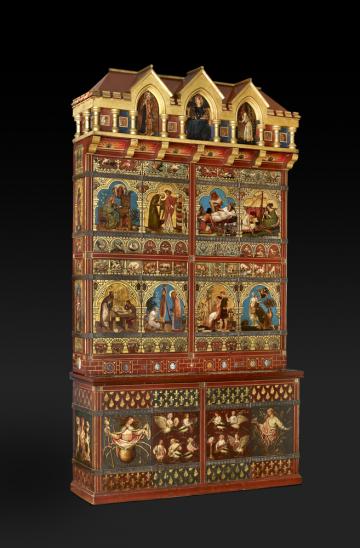

The Great Bookcase

(c) Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford

Date: 1859-62

Country of Origin: England, UK

Accession number: WA1933.26

Location: Floor 3M, Pre-Raphaelites Gallery (66)

Simeon Solomon (1850-1905) painted three of the Great Bookcase’s panels when he was in his early twenties. Described by Edward Burne-Jones as “the greatest artist of us all” [4], he was a prolific artist associated with the Pre-Raphaelites. Solomon exhibited paintings and drawings at the Royal Academy between 1858-72 and was celebrated by many of his contemporaries, including Oscar Wilde. In 1873, however, he was arrested and found guilty of attempted sodomy, followed by six weeks’ detainment and a fine of £100. He later faced a similar charge in Paris and three months in jail. This dramatically affected his wider reputation, yet he continued to produce hundreds of drawings and paintings (some of which are held in the Ashmolean’s Western Art Print Room). Solomon experienced hardships in his later life, including periods in St. Giles’ workhouse. However, the scope of his artistic skill and imagination has steadily become more widely acknowledged.

Gemma Cantlow

Images